Rubik's Cube Part 1

09 Apr 2021So I have been working on a project in the past few months. It was mostly a coding project, but due to its nature being related to schoolwork, deadlines prevented me from actually completing the project to my standards.

This will most likely be a three part series, with the first post (this one) explaining our results, the second post going deeper into the process, and potentially a third post to follow up after a summer’s worth of improvements.

This paper was co-authored by Callum Lehingrat and myself. Thank you very much for joining me on this endeavour.

The Efficiency of the Rubik's Cube

A Numerical Analysis of Rubik's Cube Speed-Solving Methods, with a Focus on CFOP & Roux

Abstract

CFOP and Roux are the two most popular 3x3 Rubik’s Cube speed-solving methods among solvers today. In our report, we seek to answer the question: with respect to varying metrics, which method is faster Our project consists of creating a large sample size of solves by creating a computer program to solve a multitude of cubes, whilst taking additional factors into account such as average move speed, which includes the average number of moves required to solve the cube, look time, finger-tricking, cube repositioning, and algorithm-specific time deductions. After we collected data from the computer using the different methods to solve one million cubes with identical scrambles, we discovered that with respect to most metrics, Roux outperforms CFOP.

Before moving on, we recommend consulting the supplemental information section of our paper at the bottom of this page, as it contains definitions of unavoidable cubing jargon used in the rest of this report.

Introduction

As newer, faster-turning models of the cube continue to be released and as solvers further optimize their methods, the world record for the fastest 3x3 solve continues to decrease [8]. Fridrich’s method, better known as CFOP, consists of solvers using an abundance of algorithms to solve the first two layers of the cube simultaneously [6], and then solving the final layer using only two algorithms [6]. On the other hand, the Roux method focuses on solving the corners of the cube first [5], and then working inwards to solve the cube by repositioning the middle pieces [5]. Both methods have their differences. On average, CFOP has a higher move count than Roux [4]. Furthermore, the Roux method makes use of moving the middle layer at a high frequency [5], whereas CFOP rarely requires such movements [6]. Furthermore, with respect to setting new world records, CFOP is the overwhelming winner [8]. Despite their differences, both methods allow solvers to employ a variety of finger-tricks, allowing for quick algorithm execution. Finally, both methods require the solver to reposition their hands several times over the course of a solve, and to look multiple times to reassess the situation.

We hypothesize that CFOP is faster than Roux, due to its prevalence in competitive solving.

Methods

Metric

Traditionally, the efficiency of an algorithm or a method is often measured in turn metrics such as HTM and STM. However, these two metrics both have basic assumptions: HTM assumes that every single face move will take the same amount of time, and middle slice turns will take double that; meanwhile, STM assumes all the moves to be equal. As we have asserted above, not all moves and sequence of moves are created equal. As such, we have identified four different factors that will affect a metric’s accuracy as a time-unit.

- Look time: The approximate amount of time (in number of moves) taken to inspect the cube and identify moves.

- Cube rotations: Since rotating a cube is not turning any faces, it is not included in any metrics. However, it still takes time to rotate a cube.

- Regrips: Some moves on the cube cannot be performed (as easily) without a regrip, which is essentially removing your hand from the cube and then placing it down differently.

- Deduction factor: When alternating moves on the same two faces, through the flexible design of speed cubes and techniques such as “corner-cutting” and “finger-tricking”, the effective time it takes is less than the actual number of moves, since they are often performed in one fluid motion.

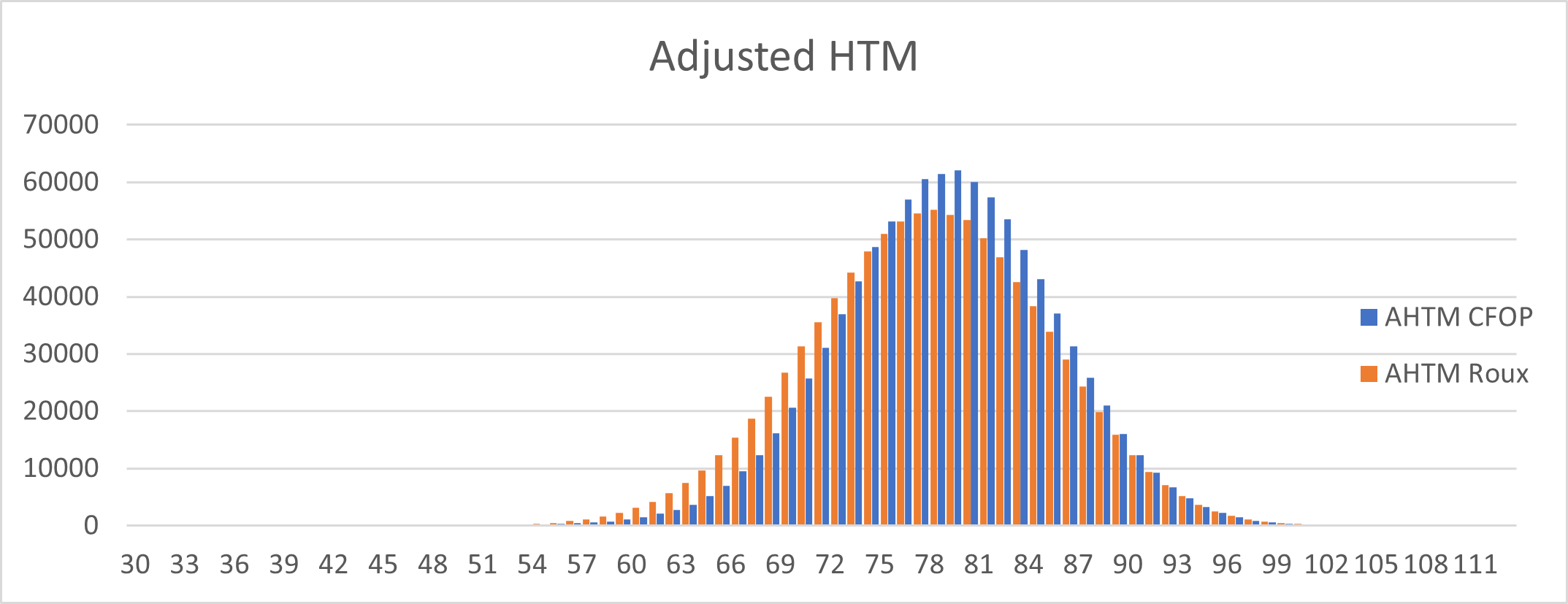

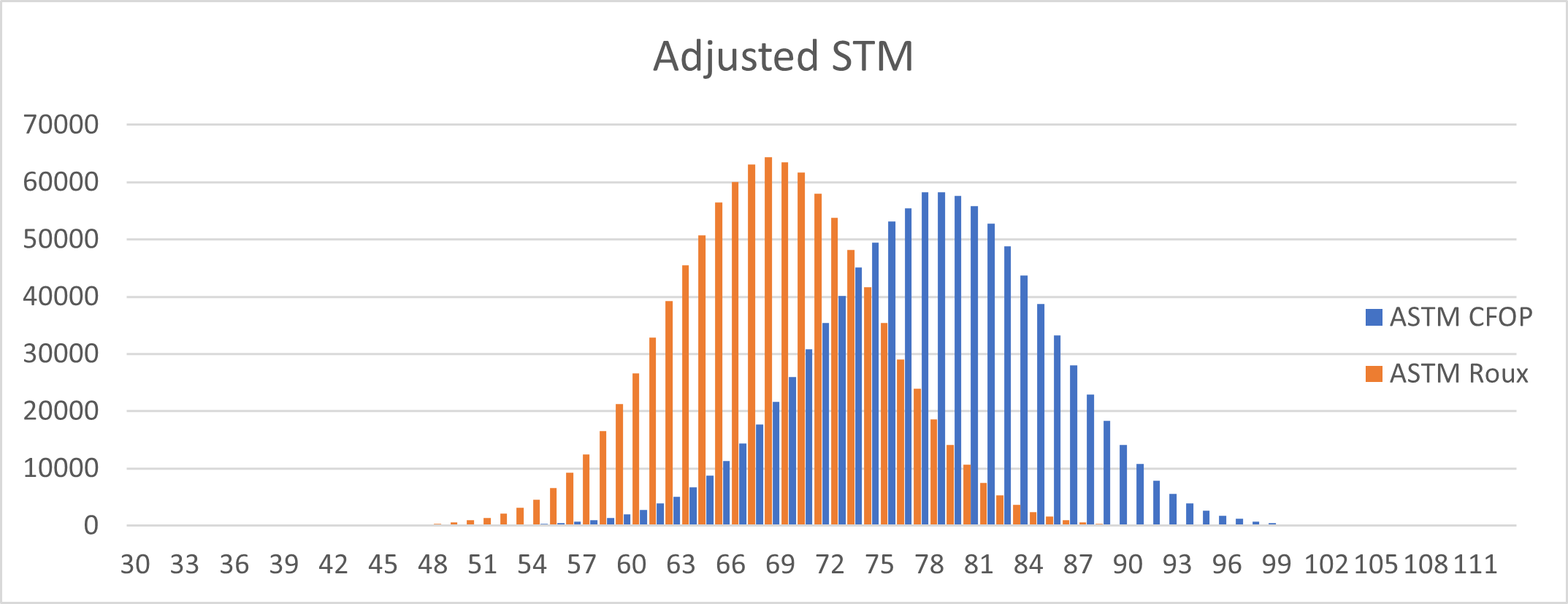

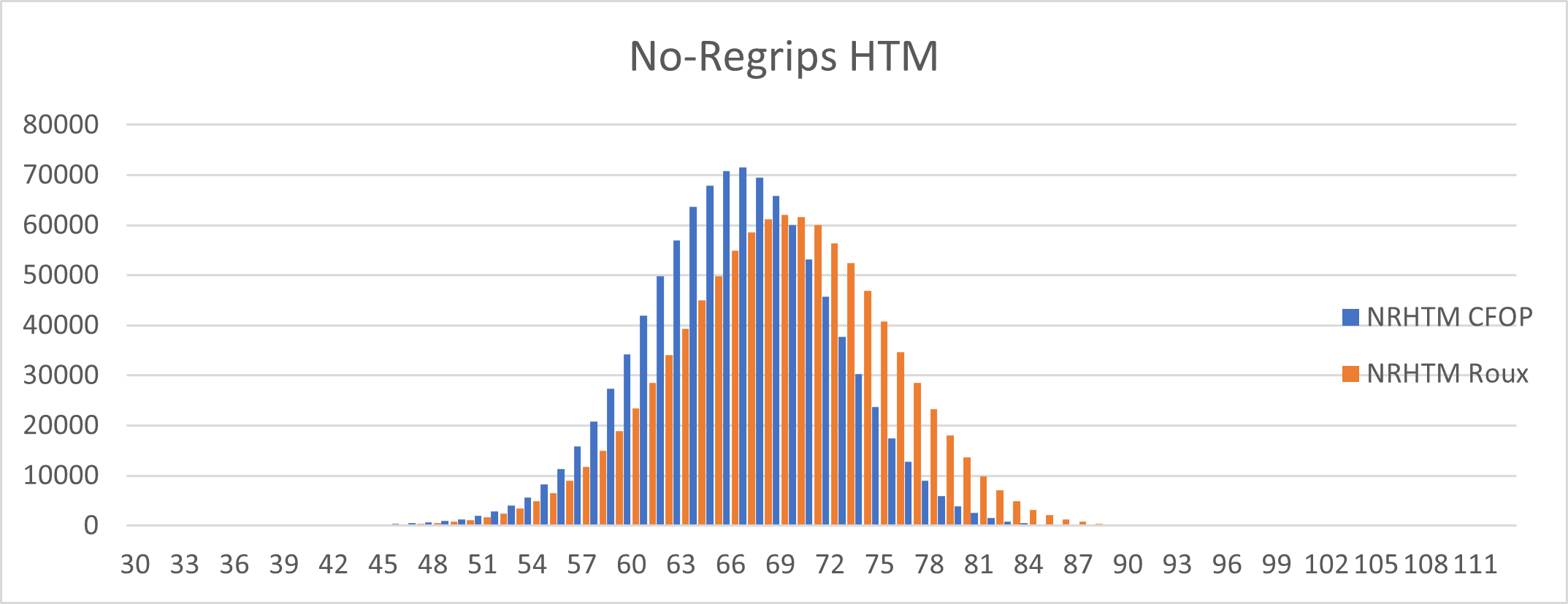

By incorporating these four factors in different proportions, we have created two corrections to be made to existing metrics. The Adjustment Factor (AHTM and ASTM seen below) adds two moves every time inspection and rotation is needed, and adds one move for every regrip; the No-Regrips Factor (NRHTM and NRSTM seen below), on the other hand, adds one move each for inspection and rotation, and ignores regrips, since at the highest level of speed-cubing, the number of finger-tricks available completely removes the need for regrips.

Code

We emulated the scrambled state of a cube and solved it while keeping track of the metrics mentioned above. This process is repeated a million times to obtain the distributions for the two methods shown below. The link to the GitHub repository can be found here.

Results

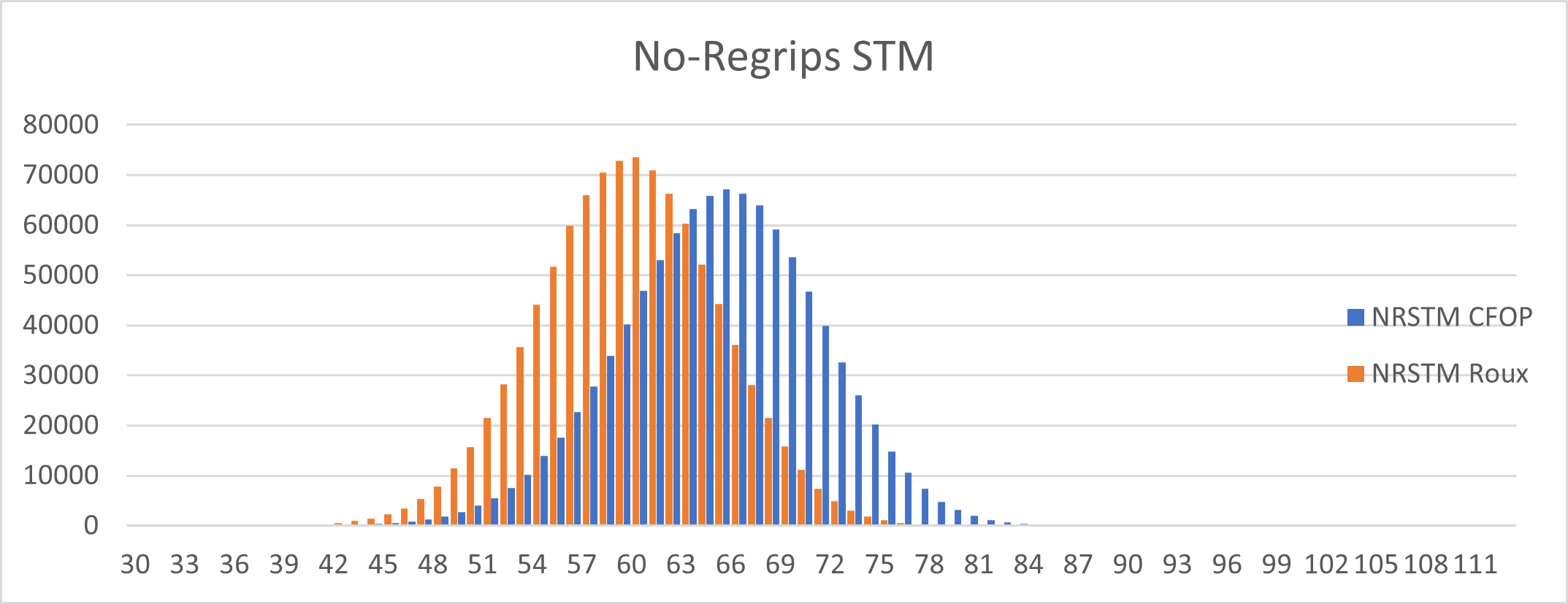

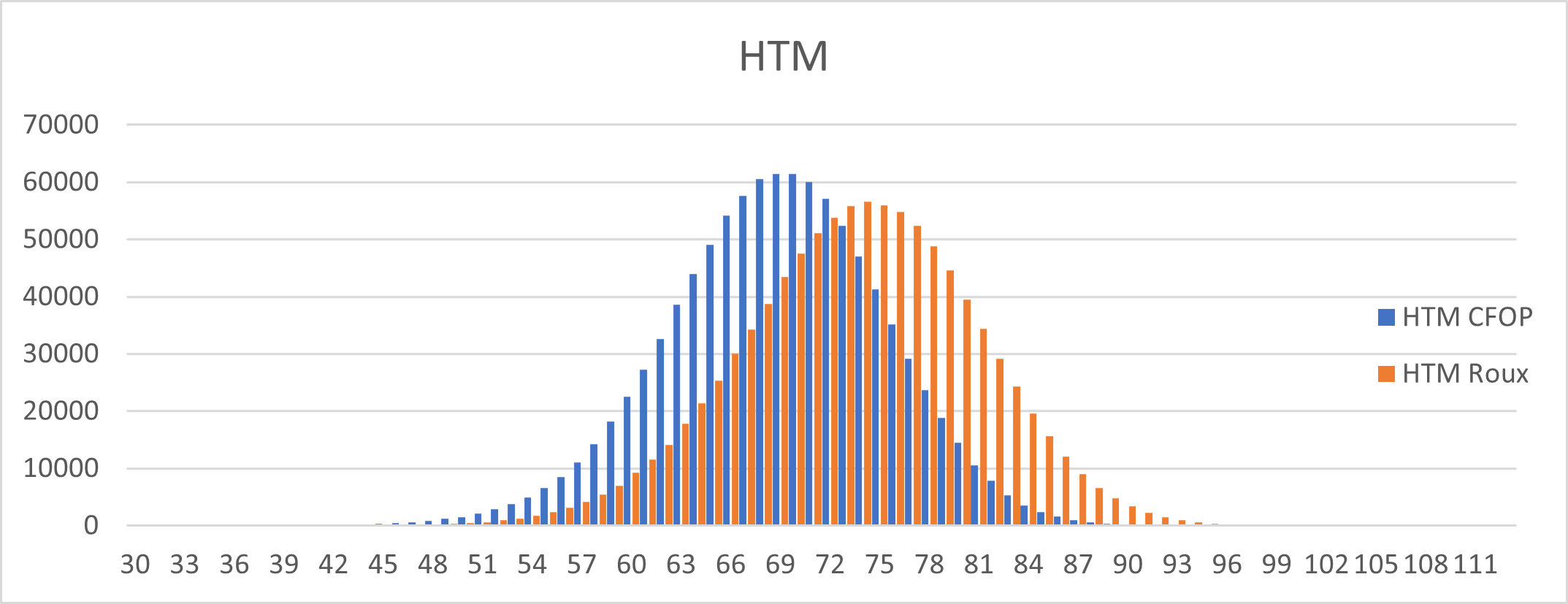

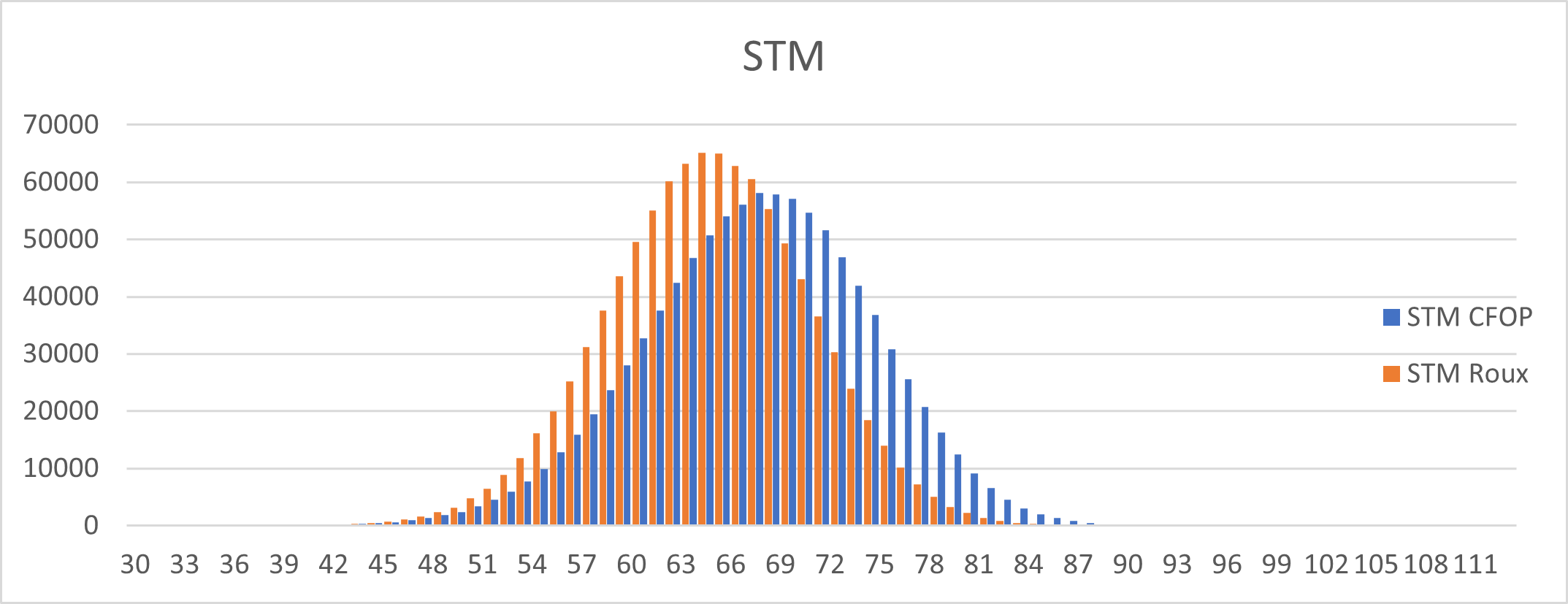

As presented above, since CFOP uses less middle slice turns than Roux, under the assumption that the two methods are equal in speed, it is expected that CFOP will generate lower values in all HTMs, and Roux will generate lower values in all STMs.

While the 3 STMs predictably favoured Roux, out of the 3 half turn metrics, only HTM and NRHTM favoured CFOP, while AHTM indicated Roux to be faster. Due to the high number of samples, the p-values evaluated from the two-tailed t-test for all six metrics is effectively 0, and we can visually identify the quicker method from the overlapping distributions.

Table 1. The means and standard deviations in number of moves of CFOP and Roux, measured in the six metrics. T-score is calculated using a paired Student’s T test.

| HTM | STM | AHTM | ASTM | NRHTM | NRSTM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFOP mean | 68.905347 | 67.962297 | 79.414499 | 78.471449 | 66.602106 | 65.659056 |

| Roux mean | 73.609764 | 64.264263 | 77.544101 | 68.198600 | 68.809291 | 59.463790 |

| CFOP SD | 6.581088 | 6.904131 | 6.531167 | 6.877734 | 5.661963 | 5.993907 |

| Roux SD | 7.116545 | 6.163162 | 7.203812 | 6.189490 | 6.428597 | 5.422036 |

| T-score | 485 | 399 | 192 | 1110 | 257 | 766 |

Discussion

The accepted average STM values for CFOP and Roux is 60 and 48 respectively [9] [10], which significantly deviates away from the experimentally obtained values of 68 and 64. This can be explained by the use of adjust U-face techniques [11], which rotate a single face instead of the entire cube to match specific cases; this takes up moves, as opposed to cube rotations, which do not take up moves, but are not widely used in actual speed-cubing, as a single move takes less time than a cube rotation.

The other source of error would be due to the not perfectly optimized intuitive steps. As we have taken an algorithmic approach to simulate these steps, it is likely that it is not the best way to do so. However, since Roux, having two intuitive steps, should be less optimized than that of CFOP, which only has one intuitive step, it is logical to conclude that Roux is quicker than CFOP.

Although the data shown suggests that the Roux method is faster than CFOP, we must keep in mind that different variations can be introduced to both methods, further increasing their efficiency and speed. Realistically, the number of variations we can use is limited by the number of cases and algorithms the cuber can memorize and perform efficiently. At the highest level of speed-cubing, cubers will seldom only use the basic forms of these methods, but rather take the approach of that method, and combine steps from different methods to decrease their solve times.

In addition, there is a historical factor involved. CFOP was first proposed in 1981 [9], but Roux was introduced in 2003 [10]. As a result, CFOP is much more researched, with more variations and algorithms discovered. This leads to a higher popularity among speed-cubers, since a lot more information surrounding CFOP is readily available.

Furthermore, although our data supports the idea that the basic form of Roux is faster than that of CFOP, we cannot recommend CFOP cubers to change over to Roux. This is because at the highest level, variations for both methods will share many algorithms. Therefore, it is unlikely that any one method will have a definite advantage over the other. However, for beginners going into speed-cubing, looking to choose a method, we can suggest Roux as a quicker method than CFOP.

Concluding Remarks

Roux is shown to be quicker than CFOP in 4 metrics out of a total of 6 measured and should be recommended to beginners. However, since speed comes with instinct, not thought, we cannot recommend speed-cubing veterans to change methods after years of practicing and training.

Jargon & Supplemental Information

CFOP (Fridrich’s Method): A speed-solving method whereby the cube is solved in 4 steps. A cross is created on one side, and then an abundance of different algorithms is used to solve the first two layers of the cube simultaneously. The final layer is then solved in two steps, first by correctly orienting those blocks, and then permuting them into the correct position [6].

Roux method: A speed-solving method whereby solvers first focus on solving the corners of the cube through the building of two sets of 1x2x3 blocks, then solve the four remaining corners, and then completing the last six edges [5].

Corner-cutting: The phenomenon in which when a side is not completely aligned, another perpendicular side can still be turned due to the flexible design of cubes. This results in a distinctive “snap” when the unaligned side clicks into place.

Finger-Tricking: An unofficial term employed by competitive cubers whereby cubers solve cubes much more quickly by the ability to turn sides with a single finger movement, rather than the movement of the entire hand [2]. This allows cubers to turn multiple sides simultaneously.

HTM (Half-Turn Metric): A metric for the 3x3x3 Rubik’s Cube where any turn of any face, by any angle, counts as 1 turn [3].

QTM (Quarter-Turn Metric): A metric for the 3x3x3 Rubik’s Cube where any turn of any face by 90 degrees counts as one turn. It differs from the half-turn-metric because half-turns (turning the same face twice) count as two moves instead of one [3].

STM (Slice-Turn-Metric): A metric for the 3x3x3 Rubik’s Cube where any turn of any layer, by any angle, counts as one turn. It differs from the half-turn metric because middle-layer turns count as one move instead of two [3].

References

1 Fewest Move Count (FMC) Rubik’s Cube Event. (n.d.). Retrieved February 26th, 2021

2 Finger tricks - Get Faster At Rubik’s Cubing. (n.d.). Retrieved March 05, 2021

3 Metric. (n.d.). Retrieved February 26th, 2021

4 Postan, L. (2021, February 07). Is the Roux Method Better Than the CFOP Method? Retrieved March 05, 2021

5 Roux Method. (n.d.). Retrieved March 05, 2021

6 Rubik’s Cube solution with advanced Fridrich (CFOP) method. (n.d.). Retrieved March 05, 2021

7 The history of the Rubik’s Cube - Timeline with important dates. (n.d.). Retrieved February 26th, 2021

8 The History of the Rubik’s Cube World Records. (n.d.). Retrieved February 26th, 2021

9 CFOP Method. (n.d.). Retrieved March 09, 2021

10 Roux Method. (n.d.). Retrieved March 09, 2021

11 AUF. (n.d.). Retrieved March 09, 2021

Figure 2. The speeds of CFOP and Roux methods over 1 million solves, measured in slice turn metric.

Figure 2. The speeds of CFOP and Roux methods over 1 million solves, measured in slice turn metric.

Figure 3. The speeds of CFOP and Roux methods over 1 million solves, measured in half turn metric with adjustment factor.

Figure 3. The speeds of CFOP and Roux methods over 1 million solves, measured in half turn metric with adjustment factor.

Figure 4. The speeds of CFOP and Roux methods over 1 million solves, measured in slice turn metric with adjustment factor.

Figure 4. The speeds of CFOP and Roux methods over 1 million solves, measured in slice turn metric with adjustment factor.

Figure 5. The speeds of CFOP and Roux methods over 1 million solves, measured in half turn metric, omitting regrips.

Figure 5. The speeds of CFOP and Roux methods over 1 million solves, measured in half turn metric, omitting regrips.

Figure 6. The speeds of CFOP and Roux methods over 1 million solves, measured in slice turn metric, omitting regrips.

Figure 6. The speeds of CFOP and Roux methods over 1 million solves, measured in slice turn metric, omitting regrips.