A Final Look at the Poincaré

01 Dec 2020I swear, this is my final post about the Conjecture. I have had enough topology for this year.

This is just a replication of my final written report that I have submitted, sprinkled with the animations that I have made for the presentation.

The Century-Old Problem

A Brief Overview of the Poincaré Conjecture and Perelman's Solution

The Conjecture

The Poincaré Conjecture, first posed by Henri Poincaré in 1904, is a problem in topology that asks whether a compact 3-manifold that allows every simple closed curve within the manifold to be deformed continuously to a point is homeomorphic to the 3-sphere (Milnor, 2004). To understand the conjecture, first we must define several terms used in the description.

A topological manifold in the nth dimension is said to “locally look like” a Euclidean space in the same dimension (Lee, 2012, p. 1). In essence, a 2-manifold “looks like” a 2-dimensional plane locally; for example, when examined at a close distance, the surface of the Earth seems flat, and therefore it is a 2-manifold. A 3-manifold, by analogy, should “look like” 3-dimensional space locally; for example, outer space can be considered a 3-manifold.

Compactness implies a manifold is closed and bounded (Lee, 2011, p. 85). A piece of paper with negligible thickness is not compact, because there are edges; however, the surface of a sphere is considered compact, since there are no edges.

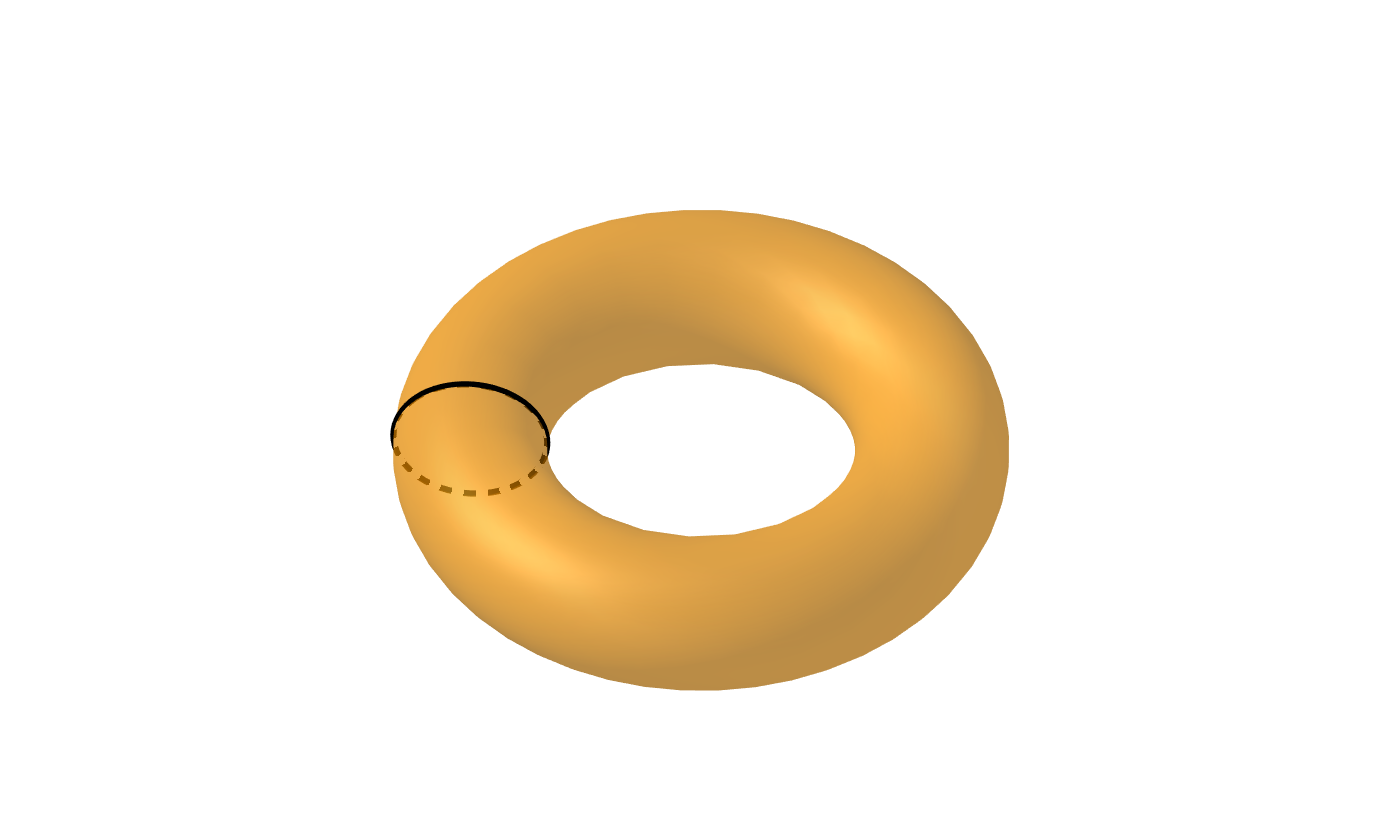

A closed curve deforming into a point can be thought as wrapping a rubber band around the surface of sphere. If we tighten that rubber band, it will glide along the surface, reducing the area inside it, and eventually tightening to a point. However, if we loop that same rubber band around a doughnut, passing through the hole, we cannot tighten that rubber band to a point without destroying the doughnut.

Homeomorphism is a continuous process that maps an object to another (Lee, 2011, p. 28). If a manifold can be stretched and deformed into another manifold without punching extra holes in it, they are homeomorphic to each other. In a classic example, since both a coffee mug and a doughnut have exactly one hole, they are homeomorphic to each other.

Finally, a 3-sphere is a hypersphere. A circle, or a 1-sphere, is constructed using all the points on a plane a fixed distance away from a single point. A sphere, or a 2-sphere, is constructed using all the points in space a fixed distance away from a single point. A 3-sphere, by analogy, is constructed using all the points in 4-dimensional space a fixed distance away from a single point. Note that in topology, an n-sphere refers to a hollow sphere, not a solid ball.

The conjecture essentially asks whether a 3-dimensional space that is curved in the 4th dimension, finite in volume, with no edges, and having no “holes”, can be stretched and shrunk to a hypersphere.

The Mathematician

For almost a century, the problem remained unsolved. The Generalized Poincaré Conjecture, the analogous conjecture for topological manifolds in other dimensions, was solved for all cases other than the 3rd dimension by 1986 (Milnor, 2004).

In 2000, the conjecture was included as part of the Millennium Prize Problems, a set of 7 challenging unsolved problems in modern mathematics. Providing a correct solution to any of the problems would yield the mathematician a prize of $1 million (Clay Mathematics Institute).

Enter Grigori Perelman. Perelman is a Russian mathematician who, unlike many other scientists and mathematicians, liked to work alone. Close friends described him as “ascetic” and “eclectic” (Nasar & Gruber, 2006). With a simple lifestyle, a firm dedication to problem-solving, and enough courage to publish a paper without seeking any review, Perelman posted his first of three instalments on the solution to the Poincaré Conjecture on the internet in 2002.

The Solution

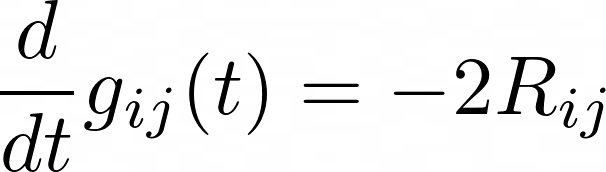

In his first paper, Perelman summarized the use of Ricci flow in reducing closed manifolds. Ricci flow is most often presented as a differential equation

where g is a Riemannian metric, and R is the Ricci curvature (Perelman, 2002). For every point, the metric outputs a scalar number that describes the curvature and dictates how it should stretch or shrink; just as how a tangent line describes the slope and dictates how functions change. Ricci curvature expresses the curvature of the manifold in terms of the metric. The equation essentially states the change of the metric is proportional to the curvature. When a region is concave, Ricci curvature is negative, Ricci flow inflates it, and the metric increases; conversely, when a region is convex, Ricci curvature is positive, Ricci flow deflates it, and the metric decreases. A sphere has positive curvature everywhere, and will therefore always deform into a single point; if any manifold that undergoes Ricci flow deform into a point, then it must be homeomorphic to a sphere. However, in higher dimensions, Ricci flow sometimes fails and creates singularities (points that are not differentiable) before a single point is produced (Milnor, 2004).

The second paper addresses these singularities and introduces a method to bypass them. Called Ricci flow with surgery, Perelman proved that all singularities can be cut and replaced with spherical caps, and then restarting Ricci flow on the resulting two manifolds (Perelman, 2003a). If the resulting two manifolds tend to a single point, then they must be homeomorphic to two spheres, and two spheres connected must also be homeomorphic to a single sphere.

A natural question that arises next regards the number of surgeries needed. If one cut can be made to a manifold, it is logical that further cuts can be made to the resulting manifolds; and if an infinite amount of cuts are made, then Ricci flow with surgery might not necessarily reduce any manifold to a sphere. The third paper proves for any Riemannian metric, the solution to Ricci flow with surgery becomes extinct in finite time, meaning only a finite amount of cuts are needed (Perelman, 2003b).

As a result, any 3-manifold can be transformed into 3-spheres through Ricci flow with a finite amount of surgeries, and therefore is homeomorphic to a 3-sphere.

The Effect

Two years passed without a single flaw was found in Perelman’s papers. The proof was then deemed complete; Perelman was awarded a Fields medal and the $1 million from the Millienium Prize Fund – but he turned both down. Subsequently, Perelman retired from mathematics, partly due to his inability to handle fame, and partly due to controversy after fellow mathematicians claimed Perelman’s work as their own original work. He was “dismayed by the discipline’s lax ethics” (Nasar & Gruber, 2006).

As of 2020, the Poincaré Conjecture remains the only solved Millennium Prize problem (Clay Mathematics Institute).

Bibliography

Clay Mathematics Institute. (n.d.). The Millenium Prize Problems.

Lee, J. M. (2011). Introduction to Topological Manifolds (2nd ed.). Springer.

Lee, J. M. (2012). Introduction to Smooth Manifolds (2nd ed.). Springer.

Milnor, J. (2004, June). The Poincaré Conjecture.

Nasar, S., & Gruber, D. (2006, August 28). Manifold Destiny. The New Yorker.

Perelman, G. (2002, November 11). The entropy formula for the Ricci flow and its geometric applications.

Perelman, G. (2003, March 10). Ricci flow with surgery on three-manifolds.

Perelman, G. (2003, July 17). Finite extinction time for the solutions to the Ricci flow on certain three-manifolds.